It’s a very rare moment when the demise of a car seemingly devoid of any redeeming features reduces two grown men to tears, but I’m happy to admit that this was the case for us. For those who didn’t have a chance to read part 1, I had chosen an 850cc 3-cylinder Daihatsu Move to transport the Monster Chef team from Melbourne to Cairns via the great Australian outback as part of the Shitbox Rally, raising money for the Cancer Council.

Even by the second day, it was clear that my co-pilot Aaron Klaver and I were beginning to bond with the car. We had already started patting its dashboard at the beginning and end of every day, and were referring to it as ‘Movey’. We had every confidence that this tiny car with its even tinier motor was going to get us all the way to the finish line. Our journey in the Move was going to be the classic ‘little engine that could’ story. The rally was not a race, but a survival test – to this end, we agreed from the outset that the only possible way the car would meet its demise would be if we were travelling too quickly for the prevailing conditions.

Day Two – Wentworth to Tibooburra

For the second instalment, we rejoin the rally just north of Broken Hill, having left civilisation, phone coverage and two-laned bitumen highways behind us. When we stopped for our obligatory photo along side the warning sign when we reached our first stretch of dirt road, we had no idea what punishment awaited us.

I’m not sure what sadistic minds wander the corridors of power in the RTA in NSW, but for some reason, the next two-hundred-kilometre stretch to Tibooburra was randomly bitumised in sections of about 3 kilometres long, as though their budget didn’t really extend far enough to surface the whole highway. Penny pinching at its finest.

It would have been bearable if it weren’t for the other 90% of dirt road being some of the worst we’d see for the entire rally. Imagine driving along a road randomly dotted with rocks the size of house-bricks and you’ll get some idea of what we were up against. With the area having also suffered recent flooding, throw in potholes around 30-centimetres deep, and washed out sections of road every kilometre or so. A revised cruising speed of just 60km/h delayed our progress, meaning the last stretch was completed right on dusk, prime time for kangaroos and other wildlife all intent on embedding themselves in our front windscreen. Tyres were shredded, fuel tanks were punctured, bump stops and other suspension components were smashed to smithereens. With Klaver at the helm and me spotting potential dangers from the passenger seat, it was some of the most intense driving either of us had ever done, and required complete concentration.

As we rolled into Tibooburra, the relief at the campsite (on the town’s horse racing track) was palpable amongst the competitors. Best mechanical repair story of the day went to the mechanics who were able to build a replacement alternator for one car with a beer can! Much to everyone’s delight, the beer-can alternator survived the rest of the trip, too. As for team Monster Chef, the mysterious power drop from earlier in the day had disappeared, and despite taking some heavy hits to the underside of the car and tyres, the Move needed little more than a splash of fuel and oil to prepare for day three.

Day Three – Tibooburra to Innamincka

The daily drivers’ briefing by organisers was long and serious. Although we only had to cover 400km for the day, the terrain was seriously hard going, with even the locals warning us that the condition of some of the roads were the worst they’d ever seen. Severe corrugations, razor sharp granite jutting out of the ground, super-fine bulldust hiding huge rocks, 10m high sand dunes, dips, washouts, pot holes – the list went on and on. After completing the regular morning checks on the Move, the next job was to drop the tyre pressures. Prior to this, we’d been running close to 40psi on the bitumen, mainly because of the heavier loads and higher speeds. Dropping this to just 26psi had a dramatic effect on the handling, making it far more predictable when changing direction and giving a much smoother ride.

Of course, in this context, the term ‘smoother’ is a fairly loose interpretation: even with a travelling speed of just 40km/h, the corrugations were the kind that shook us to the very core of our being. We could actually see the dashboard of the Move flexing at different rates to the rest of the body, so it was little wonder that the CD player packed it in after about 50km. The drumming and thumping of the tyres and suspension was so loud inside the cabin that we never heard the music coming from it anyway.

At around the 100km mark, I went to change from fourth gear back to third, and instead hit the dashboard and lost all drive. Rally organisers provided support crews to assist stranded participants, and although we were carrying a wide variety of spares inside the car, their extensive array of tools proved very handy in this instance. After a quick poke around under the bonnet, it was determined that the gear selector cable had popped out of its bracket – no big deal in the scheme of things. After about 20 minutes of filing, grunting and cable tying, everything was back in its rightful place and we were back on the move. Ironically, the gearchanges felt better than they ever had.

Cameron Corner marks the point where South Australia, New South Wales and Queensland meet, and also where rally members crossed the ‘Dog Fence’ through a very impressive looking gate with a variety of warning signs. It’s fair to say that just making it to Cameron Corner was high on our list of goals for team Monster Chef. To do so without puncturing a single tyre or having any major mechanical problems made us incredibly proud of the Move. Of course, I did my best to ruin the gravity of the occasion by planking the commemorative post, spreading my generous mid-section across three states. Having successfully avoided the great planking plague of 2011, my inaugural attempt simply reminded me, simultaneously, that I should lose weight and tone my muscles in a variety of places. As for the reaction of those around me, I got called a ‘planker’, or words to that effect.

Near the aforementioned marker is the Cameron Corner store, which is situated in Queensland, has a New South Wales post code and a South Australian telephone number. Whilst purchasing the obligatory stubby holder, we were most amused to see a light plane land on a nearby airstrip and simply taxi along the driveway leading up to the store. The pilot was even more surprised than we were, finding over a hundred crappy cars blocking his progress. A huge, very sombre sign greeted us as we entered South Australia, warning us that, because of the recent heavy rains, the road we were about to travel on was only to be used by 4WD vehicles. So we did what any level-headed outback explorers in a tiny Daihatsu would do – tried to park under the sign for a photo (unsuccessfully, only because of the ‘rear wing’) and then completely ignored its advice.

With Klaver at the wheel, the next 150km stretch was more of the same, but mixed in were slushy sections of clay and centre ruts so deep that he had to drive with the right side of the car up the top of the rut, and the left side down in the trough of the wheel tracks. The resulting angle caused the Move to adopt a stance not unlike a dog taking a leak. Despite this, it kept powering along at a time when other vehicles around us were dropping like flies, and it was fantastic to experience a lush green outback in full bloom courtesy of the storms the previous week. For all its infamy, hitting the Strzlecki Track turned out to be a godsend in terms of road condition. The road trains that regularly ply the route had packed the gravel down to a near-bitumenesque surface, although there were still washed out sections that meant getting hard on the anchors to avoid losing the entire underside of the car.

In one of the more bizarre moments of the rally, we came over a crest, in what could reasonably be called the arse end of the earth, to find the bustling mining city of Moomba, complete with a rather large commercial passenger jet taking off just over our heads. Although closed to the general public, the stark nature of its surroundings made us feel like we’d landed on Tatooine, ironically with a fair bit of scrap metal in tow. Like most of our competitors, our arrival at Innamincka (population 15) right on dusk culminated in joyous whooping and hollering at having survived another day of mechanical torture.

Day Four – Innamincka to Windorah

While our campsite by the banks of Cooper Creek was very picturesque, sleep was rather hard to come by when the world’s largest plague of mosquitoes descended upon our group during the night. Much to my amusement, my co-driver had failed to protect himself adequately and subsequently awoke resembling a pimply-faced teenager. Whilst I managed to avoid the advances of our ectoparasitic friends, the howls from a pack of wild dingoes nearby ensured I was up at the crack of dawn.

The Move fired up with a fairly rough idle, which we attributed to the fact that, having completed the previous day’s run on one tank of fuel, it was effectively running on fumes. With fuel on the wrong side of two dollars per litre at Innamincka, it would have been far more painful if we’d had to purchase more than the twenty-eight litres it took to fill the tank! We received another full complement of warnings about the state of the roads for today’s 450km leg, and the first stretch of road to the SA-Qld border was astoundingly rocky, to the point that we were increasingly worried about the precarious positioning of the Move’s lower control arms, sump and fuel tank. In a classic display of interstate one-upmanship, we crossed the border and arrived at the smoothest bitumen road for the entire trip. I suspect I may have been the only person to ever sing Anna Bligh’s praises at that point.

Having bumped our speed back up to 100km/h, a mysterious power loss issue from early on day two soon returned, and then, just 30 kilometres from Innamincka, the Move dropped a cylinder. Bearing in mind it only had three cylinders to begin with, there was no way we could maintain forward progress with a full load of passengers and gear. Event organisers had arranged competitors into groups of around eight cars each, and in Group 16, there were a couple of seasoned mechanics as well as amateur spanner-twirlers. All jumped in to help fix the problem, consistent with the “never leave a man behind” mantra our group had adopted. Removal of the spark plugs brought howls of laughter, as they resembled barnacle-covered wharf pylons. Nevertheless, a fresh set didn’t fix the problem, and the dead cylinder was getting plenty of spark and fuel, so we were none the wiser.

We staggered a little further on two cylinders, but given that we were about to hit the dirt again, we opted to park the Move and wait for the service crews bringing up the rear of the field. Little did we know that they were still busy repairing vehicles from the night before, and that we’d be stranded for nearly two hours before they reached us. Even in April, the heat of the day baked us gently in the car, and given that the Move had expired right near the Burke and Wills Dig Tree, I tried to channel their pioneering spirit. By the time the service crews arrived, shooting a camel and drinking my own urine had become viable options.

After more tinkering and head scratching, it was clear that the cause of the dropped cylinder couldn’t be found until we’d reached Windorah, and with four of the five car trailers already filled with other dead vehicles and more dramas awaiting the service crews, it was agreed that we should see how far we could get under our own steam. Klaver was soon jettisoned from the passenger seat, reducing the total weight of the vehicle considerably (sorry Aaron!), and to reduce the drag on the motor, the spark plug and lead were removed from the dead cylinder and cable-tied to the radiator support.

And thus began one of the most challenging drives of my entire life. Imagine, if you can, the scenario: with only 31kW and 67Nm of torque from the factory, I guessed I had less than half than these figures to work with, and with the spark plug out, the resulting clatter was akin to a chaff cutter with the volume on eleven. Maximum speed was around 60km/h in third gear, although this was dependent on the viscosity of the road surface, and while hitting 70km/h would mean a change up to fourth gear, the engine never had enough torque to hold it there. Maintaining momentum was paramount, but I couldn’t hit some sections of road too hard for fear of destroying the car. I distinctly remember arriving at dips and washouts way too fast, without lifting off the throttle, hoping and praying I’d make it through unscathed.

Further along, the Move died again, and after more diagnostics and swearing, we eventually realised it had run out of fuel, despite a quarter of a tank still showing on the gauge. Evidently a big hit from day two had dented the fuel tank upwards, a bit like squashing a Coke bottle. For the first time in the rally, we opened our jerry can. Further along, we regularly came face-to-face with some very large beef cattle blocking the road, and not entirely keen to get out our way. As annoyed as I was that they’d slowed me to a near-standstill, I also quickly realised most of the bulls were larger than the Move!

Day eventually turned to night, which again meant having to be on full alert for native wildlife intent on becoming the Move’s new bonnet emblem. Not so easy when the headlights were designed for the well-lit streets of Tokyo rather than the Aussie bush. Behind me, my Group 16 team-mates were having problems of their own, with one Falcon driving without any headlights for the last stretch, relying on the cars in front for guidance. One last stop for a splash of fuel from a jerry can revealed a push-start-assisted 0-60km/h time of 1m35s!

For the vast majority of rally participants who’d arrived at Windorah hours ahead of us, they heard the faint clatter of the Move from about five kilometres away. By the time we’d reached the town, most were aware of our story, and as I steered Movey into the rally campsite, near on three hundred people rose to their feet and gave us a standing ovation. It was a hero’s welcome; a fitting tribute to a wounded soldier that had survived seemingly insurmountable odds. We had travelled over 400km and taken almost eight hours.

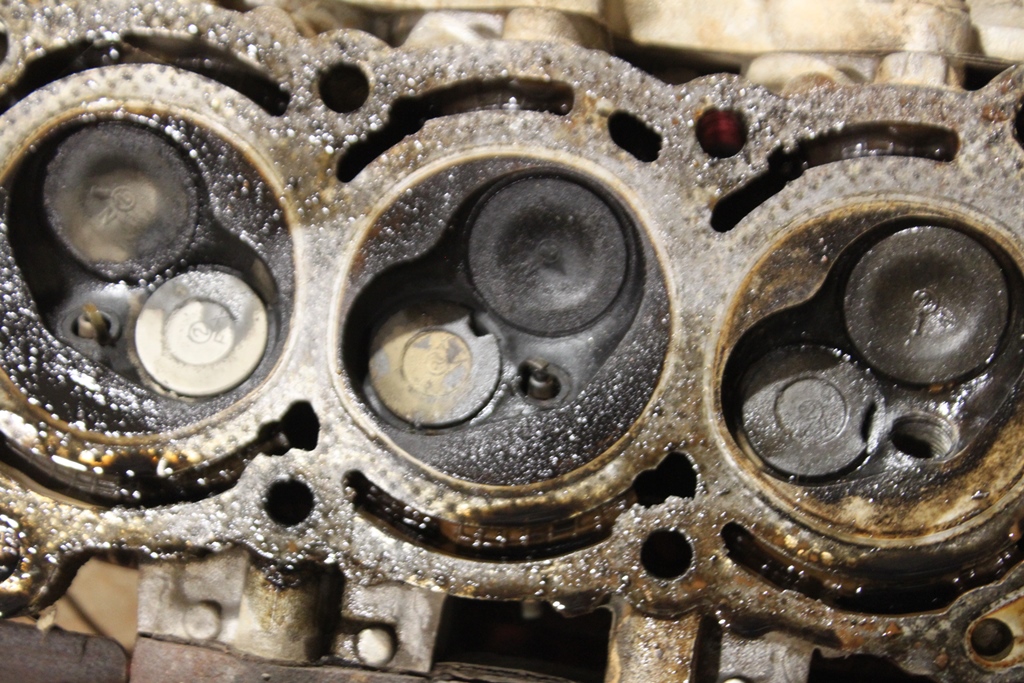

After dinner, we set to work, armed with a full array of tools. The compression tester was first up. Cylinder three was fine at 130psi and cylinder one (the dead one) came back at just 30psi. The surprise of the night was that cylinder two gave a reading of just 45psi! Although it was still firing, it was effectively as dead as its neighbour. Jaws hit the ground as we realised we’d completed the day’s run on just one working cylinder. If only Windorah had a dyno handy, the Move would surely have returned a kilowatt count in single figures.

The compression results left us with a bit of a conundrum. It was clear that the problem was serious, more serious than we’d expected, but given that we were at the most remote point of the rally, we could either continue as-is the following day and see how far we could get, or roll the dice, pull the head off the motor and try and fix the problem with the resources we had available to us. Convinced we’d done a head gasket, we went with the second option, thinking we could create a replacement gasket with some thick aluminium sheet we’d nabbed off one of the other teams.

As the moment of the ‘grand reveal’ arrived, what little space there was under the Move’s bonnet was packed with heads hoping to get a glimpse of the damage. The reaction as the head came off was priceless, with many backing away from the car in shock, as though they couldn’t face the horror. The head gasket looked like it was virtually brand new, but delving a little deeper revealed two of the three exhaust valves were completely burnt out, lodging bits of themselves in the catalytic converter. Our worst fears had been realised. Even if we’d been able to successfully reassemble the motor and not kill the one ‘good’ exhaust valve, the nearest Toyota dealership (who now supply Daihatsu owners with parts in Australia) at Longreach was another 320km away, a massive diversion from the rally’s route, and even then, exhaust valves for an 850cc Daihatsu engine were hardly the kind of parts they were likely to have in plentiful supply.

Our options were all but exhausted (no pun intended). Klaver and I approached the rally director to get his verdict on what we should do next, and his response was like a knife through the heart: “Bury it.” And like that, our rally was over. The Move was pronounced dead. Our brave soldier, that had battled so valiantly despite a terminal heart condition and returned to hero’s welcome, breathed its final breath and in one last great act of selflessness, donated its organs so that others might live. Within minutes, the other teams had gathered around Movey like vultures, stripping it of parts to help repair their vehicles.

Still in shock at its death warrant, seeing my little battler being ruthlessly torn apart was too much to bear. I grabbed a beer, walked away from the campsite, sat alone and shed many a quiet tear. Klaver’s turn came the next morning when we farewelled the car, adding “It’s just not right.” I completely understood. As owners of businesses devoted to the preservation of cars, leaving a dead car by the side of the road just wasn’t in our nature.

First published in ‘High Performance Imports’ magazine, August 2012.

Fancy some extra special bonus content that never made it into the magazine article? Find out what happened next in the third instalment.